How One Farmer Built A Dairy Dynasty In India

By Carl Peterson, Cargill Contributor

In the world of sports, it would be called a dynasty. For Harpreet Singh, a dairy farmer in northern India, his farm’s streak of dominance for milk production at the state fair is just business as usual.

“Normally, we get the first rank, but in some shows we get second or third,” he said. “Last year, among the top 10 cattle in the show, five were from our farm!”

His animals average 36 liters of milk per day, well above a national average that’s less than 10. And his champion cow can produce up to 60 liters, an amount described as “unheard of” by Achyuth Iyengar, head of Cargill Feed & Nutrition for India.

“If Cargill had not been there, we would not have been able to get the production we have today,” Singh said, referring to the 8,000-liter daily milk average that his farm generates. He has seen a rise of about 25 percent in his productivity since switching several years ago to Cargill developed feed products like Purina® Milkgen 10000. Along the way, he has gone from 20 animals to more than 100.

But the rise in productivity for Singh and his neighbors is due to more than just converting to Cargill-formulated feed. It’s the result of a comprehensive program the company has developed around farmer training, one that’s helping transform livelihoods for as many as 75,000 farmers here every year.

A thirst for knowledge

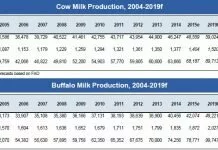

India has seen significant development in its dairy industry over the past few decades, going from painful shortages to being the largest dairy producer in the world. States like Singh’s home of Punjab and neighboring Haryana and Rajastan have become key dairy regions.

Today, India’s demand for milk is estimated at 155 million metric tons per year. Within eight years, that’s projected to grow an additional 50 percent. The most environmentally, socially and economically sustainable solution to meeting this massive need will be to help India’s small dairy farmers get more milk from every cow.But this high level of growth has not kept pace with the blistering rise in demand. The country’s rapidly increasing population coupled with higher incomes means more and more Indians want to consume protein. And because a large percentage of India’s citizens are vegetarian, many of them look to dairy products to meet that need. Milk-based paneer, ghee, yogurt and sauces are all staples of daily life.

“Here’s the irony: India has more dairy cows than any other country. We need to help make those cows more productive,” said Iyengar, referencing the fact that India’s cows often produce just a tenth of their counterparts in developed markets.

When Cargill entered India’s dairy feed market in 2006, many farmers had just a few cows, each often producing just two to six liters of milk per day, barely enough to provide for their families’ needs, let alone generate a surplus to sell. Eighty-five percent of India’s milk comes from these small farms, meaning there is huge potential if they can collectively raise their yields.

“Predominantly, farmers in India are still subsistence farmers, two- to five-cow farmers. But they have ambition,” said Iyengar. “These are people who really want to adopt new technologies to grow their herds and grow their yields, and who take pride in their own achievements.”

To help them reach their goals, Cargill began sending sales people and veterinarians to work individually or with small groups of farmers on animal husbandry practices. Topics included how, what and when to feed animals, breeding management, sanitation and animal health, among others.

Over time, these training sessions were opened up to more farmers in the communities. Today, they might be as simple as half a dozen farmers meeting under a tree, or as large as 100 to 200 people at a school or community center. Cargill often relies on lead farmers like Singh to help organize, promote and lead the sessions.

“It’s easy just to focus on increasing milk production, but some of these disease issues eat away at the farmer’s profits just as much,” said Robert Schubert, managing director of the Cargill Premix & Nutrition business that also works with India’s dairy farmers. “Addressing all of these factors can help raise their livelihoods, and the farmers have someone who they can trust to help them in a more holistic manner.”

The thirst for knowledge has proven to be nearly insatiable. Two years ago, Cargill held 600 training sessions. Last year, that doubled to 1,200. In 2016, the company will host about 3,000, reaching 75,000 farmers.

Along the way, the business also began a text messaging program that provides weekly farm management tips to more than 30,000 dairy, aqua and poultry farmers, with a goal of eventually reaching more than 100,000.

A new investment

The farmer training program has been so successful, demand for Cargill feed has surged in India.

“We have experienced phenomenal growth. We have doubled or tripled our volumes in the last few years by working at the grassroots level,” Iyengar said. “Seeing that change right in front of your eyes, that’s exciting!”

But until now, the feed has been produced in other countries and shipped in.

To satisfy the continually growing needs of local farmers, Cargill broke ground in 2014 on a state-of-the-art feed mill in Bathinda, in the southern part of Punjab. The facility, which opened in July, will produce 10,000 metric tons of feed each month, expandable to 20,000 in the future. This translates to feeding 75,000 cows on an ongoing basis.

It also will employ about 200 people on site, and provide a new market for the crops of more than 3,000 local grain farmers. And perhaps most significantly, it will offer Cargill a showcase center where farmers can visit and see first-hand the practices and products the company promotes.

Although the mill is the capstone to nearly a decade’s worth of effort to establish a strong animal nutrition business in the region, Iyengar is optimistic about the odds for continued growth.

“It won’t take us another nine years to build the second mill!” he quipped.

For his part, Singh continues to pursue his ambition of growing his farm to 200 head and beyond. He has become somewhat of a celebrity at the state and local fairs, where the yields of his champion cows provoke looks of disbelief. He was especially proud when his son Onkar attended a recent event and got to see him win.

As for his animals’ nutrition needs, he has no doubt whom he will count on for expertise.

“I don’t have to worry about nutrition. I just leave that worry to Cargill.”

Comments

comments