It’s unfortunate that India doesn’t respect buffaloes

“I can see no limit to this power, in slowly and beautifully adapting each form to the most complex relations of life.”

– Final Chapter, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, Charles Darwin

One sunny October morning in 1859, slouched on a mahogany armchair placed at the corner of a busy Pembroke table in his study, sipping on his last cup of tea before lunch, thinking of the closing chapter of his manuscript, was Charles Darwin. The tea was black. He had had to cut down on his milk and cream intake to help alleviate his chronic ill-health due to painful episodes of indigestion.

The fruity whiffs of scotch cake being baked for supper must have travelled from the tall windows of Emma Darwin’s kitchen to the study, to inspire her husband to sum-up the theory of evolution in a line as flowing as the one above. Either that or the black tea, to which he was adapting to swiftly.

Darwin wouldn’t have had a clue then, of course, but it’d have warmed the cockles of his heart to know that the very gene that caused him discomfort for life – the one responsible for digesting milk sugar or lactose – would become the living proof of demonstrating 11,000 years of human evolution in action, as published in the November 2016 edition of the journal Science.

The 11,000-year mark on the evolutionary clock corresponds to pre-historic times – the Neolithic age of our hunter-gatherer ancestors for whom milk was a harbinger of illness, except for their breast-fed babies.

One man’s milk is another man’s poison

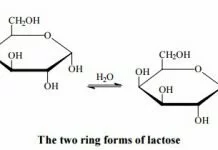

Until the end of the last ice age, human adults could not tolerate milk. Weaning children off mother’s milk would switch off the gene for lactase, the essential enzyme required to break milk sugar into its digestible forms. Several thousand years later, man turned into a farmer, then a cattle herder, and learnt to ferment milk into digestible forms such as yogurt or cheese with substantially reduced levels of lactose. These were nutritious back-up options for survival, when confronted with harvest failure or grain storage mishaps.

Around the 7,500-year mark, the lactase gene in humans mutated in Europe, triggering a gradual build-up of lactase-persistent populations that could enjoy the goodness of milk from infancy through adulthood – a favourable adaption, standing true to the principle of Darwinian fitness under natural selection pressures. Thereafter, the dairy-tolerant diaspora spread fairly rapidly across the world.

Today, 35 per cent of the world’s adult population can tolerate milk because they carry the gene for lactase production during adulthood. As for the remaining 65 per cent, milk-based products subject them to unpleasantness and diarrhoea with varying degrees of severity depending on their genetic make-up. They can, however, consume fermented forms of dairy products without riling the gut.

Unsurprisingly, as evident in the rich Indian cuisine, Indian diaspora can be placed in the high to medium range of milk or lactose-tolerant people. Up to 67 per cent of north Indians are able to digest milk without falling sick, the statistic being diametrically opposite for south Indians, with 67 per cent being genetically intolerant.

Holy cow!

Meanwhile, the hoofs clattered along, matching our direction and pace in the evolution parade. The milch animals co-evolved, adapting their genes to the domestication-associated culture, and diet changes determined by migration pattern of their keepers.

The most notable mutations resulted in differences in the protein and fat composition of their milk, and production yields. Cattle genetics has been a niche subject of socio-economic importance, particularly for the dairy industry in its endeavour to design exotic animals by cross-breeding for increased milk production.

The success of India’s Operation Flood was a result of such cross-breeding of indigenous dairy cattle with high-yield, foreign breeds, such as Holstein Friesian and Jerseycows – this transformed our milk-deficient nation into the world’s largest milk producer within 20-25 years.

Of late, cattle genetics has entered into living room conversations in the West because of its link to public health. The concern is that the breed of cows or buffaloes your milk is obtained from determines whether it is a tonic or curse for you, the operator being beta-casein (a major milk protein).

In the last decade, strong scientific evidence has established that the A1 variant of beta-casein in milk puts one at risk of a range of health issues such as diabetes, cardiovascular disorders, autism, and other aggravating neurological disorders.

Milk with the A2 variant of beta-casein still holds good to the universal and age-old status of it being a wondrous elixir. A2 milk scores over A1 milk in its ability to promote glutathione production in the body. Glutathione is a powerful antioxidant and shields us from serious diseases.

Milk of ambrosia

“Blessed am I that I am born to this land…” – Rabindranath Tagore

Using an intensive gene-typing exercise, scientists from the National Bureau of Animal Genetic Resources, Karnal, have reported that all breeds of indigenous cows and buffaloes in India are pure A2 milk type. This implies that 72 per cent of the total population of milch cows in India (Livestock Census, 2012) produces purely A2 type beta-casein rich milk, being of indigenous breeds. The rest 28 per cent of the cows are the cross-bred varieties, whose milk has varying ratio of A1 and A2 beta-casein.

It is not common practice for dairy farmers, cooperatives, and private dairy operators to tag and segregate their milch animals by breed. Anyhow, milk from small-scale suppliers gets pooled at cooperatives and large dairies. Thus, several of us have most likely been consuming a blend of A1-A2 milk products except those who have been strictly using buffalo milk as a matter of choice or chance – the entire population of Indian milch buffaloes is formed of indigenous, A2 milk producing breeds.

Those of us who consume cow milk products sourced from small-scale local dairies, and living in Assam, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, are fortunate: more than 85 per cent of the total milch cows in these states carry the indigenous A2 type genes.

For Punjab, Kerala and Tamil Nadu, however, the same ratio stands below 30 per cent, which is comparable to that of New Zealand, Australia and the US (the other large milk producers of the world), with a predominantly A1 livestock composition made up of Holstein Friesian, Ayrshire, Brown Swedish, Guernsey and Jersey breeds of cows.

Advantage India

Last month, Amul invited Prime Minister Narendra Modi to launch its packaged A2 cow milk – the first in the Indian market. This event ignited a debate in the dairy sector – how wise and economically feasible is it to create a new market segment with a product that is undoubtedly superior, but rather hard to procure due to much lower yield (by a factor of 10) of indigenous cattle breeds.

The Centre’s encouragement and support to A2 milk products and productivity improvement of dairy animals (eg through the Rashtriya Gokul Mission) is being viewed by the industry as a form of boastful exhortation or worse, coercion. But with 84 per cent of our dairy animals (cattle and buffaloes) being indigenous, the enraged reaction against the government holds little base. Seldom do we see public policies being rolled that are evidence-backed, and devoid of political or religious colour. This is one such,and it should be encouraged.

Sure, the market-enforced increase in demand for A2 milk products will come as a setback to small herd owners in the unorganised sector and bigger players alike, whose primary source of raw milk procurement is from predominantly cross-bred cattle.

The business-savvy ones will show foresight – not to whine but to collaborate with the government, and warm up to implementing extrinsic methods for yield improvements of their genetically-hardy indigenous breeds.

A huge untapped opportunity lies before India, to capitalise her evolutionary endowment, and capture the growing demand of A2 milk in the international market – in Europe, US, Australia and New Zealand (along with those nations that import milk from these milk-producing nations) primarily because the cattle breeds of these regions produce A1 or a mix of A1-A2 milk.

Our buffaloes offer an immediate solution to kickstart the A2 milk products enterprise. With high-production yields, and a nutritional quotient on a par with A2 cow milk, it would be sacrilege to continue viewing them as second-class inhabitants, both culturally and economically. A few dairy farmers of UP and Haryana have already shed the quasi-racism by extending equal reverence and love for the humble buffalo.

The other imperatives for success are better feed management, effective breeding programmes to propagate A2 genes, and strict implementation of best practices in farm management for veterinary health. With equal participation from the government and the industry, India can make its strong position more formidable in the world dairy trade.

To start with, let’s begin the exercise of updating the livestock census with genotypic profiling of our gifted friends from nature, and announce it to the world that we are the biggest producer of A2 milk. Prosperity is sure to follow.

Comments

comments